Yee, Haw! Don’t drink the water

The beauty of autumn, the kindness of strangers, and a dash of industrial by-products.

Late October is a perfect time for hiking in the mid-Atlantic. Fall colors, cooler weather, and in a warm spell the trees are still full enough for shade. Still plenty of daylight; who wants to hike more than eleven hours anyway?

But there is always a fly in the ointment, and this time of year, it’s Daylight Savings Time. In order to beat the rush hour traffic out of Raleigh, I need to leave my house by seven. That means walking the dogs at six thirty, when it is still starry-dark outside. One of my dogs is particular about where and when he does his business, and on pre-dawn walks he is apt to stop, half-squat, stand again and look at me regretfully. This ain’t right, boss.

It has been cold, too, some of these mornings. By the time I started hiking a little after eight, the sun still hadn’t cleared the treetops; one morning it was twenty-eight degrees when I set out, on a day predicted to be sixty and sunny. Half an hour’s extra sleep would have saved me a layer of clothes and ten stiff fingers.

By any reasonable diurnal mammal’s standard, my dog is right. But humans, though mammalian and biologically diurnal, are apt not to be reasonable. We think we’re clever because we’ve figured out that the earth goes around the sun and not the other way round, but any medieval geocentrist could have predicted the dawn. We think we control time, but in reality, we’re just pigheaded.

I had a bit of luck in October. A new section of trail along the Haw River had opened just three days before I came to hike, and I learned about it only because a county parks employee—I learned later that he is a “technician” and not a ranger—saw me perusing the trail map at the Shallow Ford Natural Area and told me about the new addition. A spur eight-tenths of a mile long, for now a dead end, but one day to connect further upstream. It is a matter of buying land and easements; the money is there, but some owners won’t budge. “They’ll still have full use of the land,” the not-ranger told me, “and we’ll take care of it for them.” And, as we agreed, serious hikers clean up after themselves; trash left in parks is nearly all at the edges. Still, there are holdouts.

All anybody wants is to walk along the riverbank. Eventually, it is hoped, they will be able to walk seventy miles along the riverbank, from Haw River State Park north of Greensboro near the river’s origin to Jordan Lake east of Pittsboro, not far from where it joins the Deep River to become the Cape Fear. In the meantime, I’ve walked about nine miles of it on my way eastward.

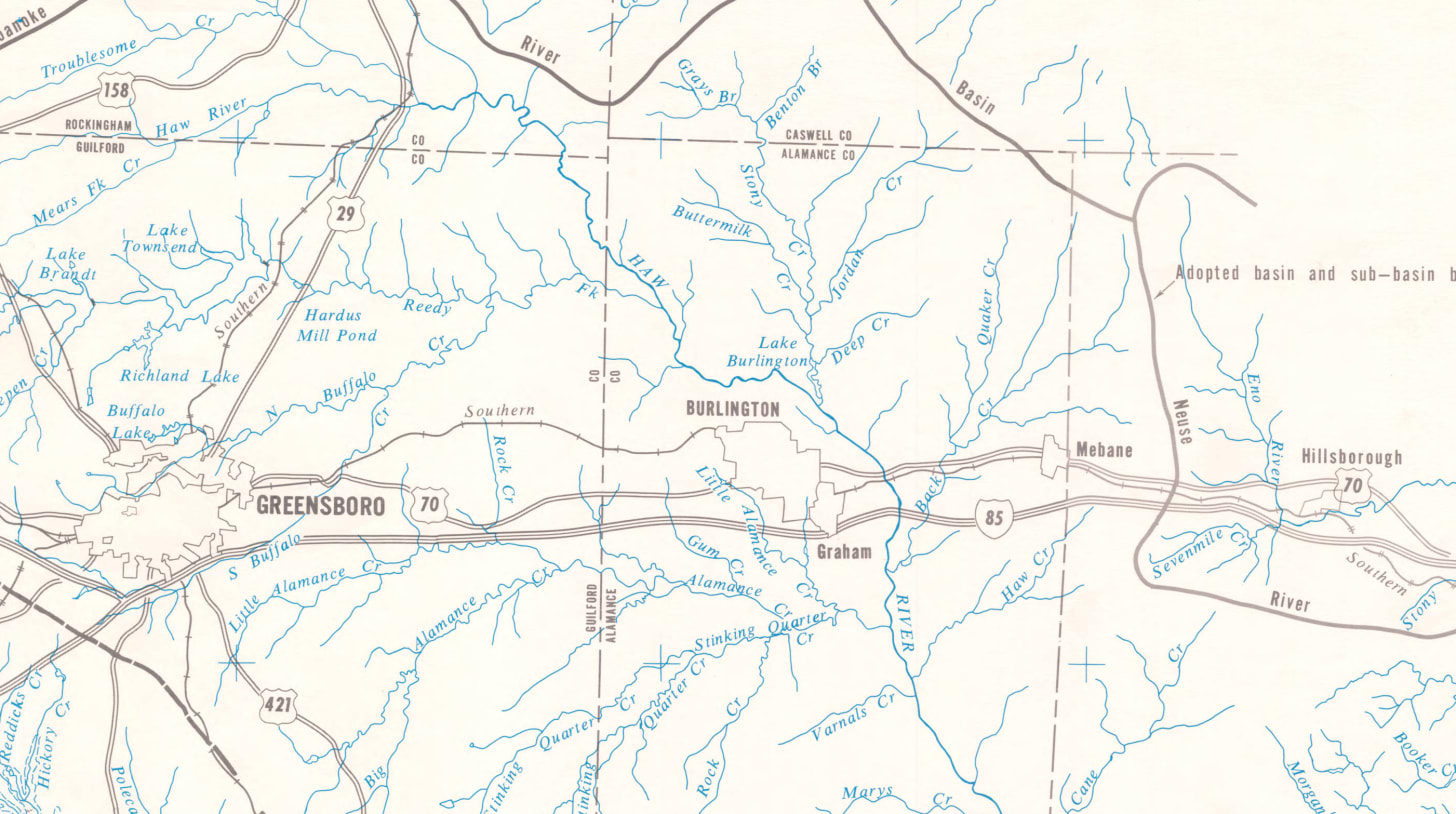

Some geography is in order. East of the mountains North Carolina’s river basins run mostly northwest to southeast, and so the MST crosses several of them. (West of the mountains, the rivers run westward, towards the Mississippi and the Gulf of Mexico.) In Guilford and Alamance Counties I have been hiking through the Haw River basin, which is part of the larger Cape Fear River basin. In Durham and Wake Counties, the Eno River and Falls Lake are part of the Neuse River basin.

In a couple of weeks I will cross the ridgeline that divides the Cape Fear and Neuse River basins. I’m hoping there will be a sign marking the watershed. Maybe I’ll take my kazoo and blow a fanfare. I have crossed county lines, but those are arbitrary. A river basin is a fact of nature.

The Haw, like the Eno, is a rocky Piedmont river once teeming with fish and perfectly suited to mills. The Sissipihaw people, who shared their name with the river, took advantage of the fish. Or Saxapahaw, as the town spells it; the name meant “step-hill” or foothill—Piedmont, in essence, and “Haw” is a traditional shortening. Like the Occanneechi, they spoke a Siouan dialect, had long resided in the Piedmont, and lived by a combination of natural harvest and agriculture. John Lawson met them in 1701:

We pass’d through a delicate rich Soil this day; no great Hills, but pretty Risings, and Levels, which made a beautiful Country.... At last, determining to rest on the other side of a Hill, which we saw before us; when we were on the Top thereof, there appear’d to us such another delicious, rapid Stream, as that of Sapona, having large Stones, about the bigness of an ordinary House, lying up and down the River.... [T]he Swiftness of the Current gave us some cause to fear; but... with great Difficulty, (by God’s Assistance) got safe to the North-side of the famous Hau-River, by some called Reatkin; the Indians differing in the Names of Places, according to their several Nations. It is call’d Hau-River, from the Sissipahau Indians, who dwell upon this Stream, which is one of the main Branches of Cape-Fair, there being rich Land enough to contain some Thousands of Families; for which Reason, I hope, in a short time, it will be planted.... Here is plenty of good Timber, and especially, of a Scaly-bark’d Oak; And as there is Stone enough in both Rivers, and the Land is extraordinary Rich, no Man that will be content within the Bounds of Reason, can have any grounds to dislike it.

The “thousands of families” Lawson predicted took advantage of the Haw’s tumbling cascades to build gristmills. Now the gristmills are piles of stones, and charming in their decay. But—as I wrote before, about the Eno and Falls Lake—some locations spawned greater mills. After the Civil War the textile industry grew up in this region, and several large textile mills used the Haw for power—eight in Alamance County alone. The industry largely defined the northern Piedmont for a hundred years, and then fell, like the Sissipahaw, to a new wave of globalization.

Chemical discharge from the bleaching and dyeing of fabric once made the Haw River, as one resident recalled, a different color every day. Now the river has been cleaned—mostly—of the textile industry’s pollution, its grounds are open for walking and paddling, and some of the old factory buildings are being converted into (of course) loft apartments.

Anticipating that twenty-eight degree morning I went to REI for a long-sleeved wool t-shirt, which sounds like a luxury but is a godsend when you are both cold and sweating. While I was there I decided, in anticipation of backpacking, to invest in a water filtration system. For less than fifty bucks you can buy something that makes the dirtiest river water drinkable and collapses to practically pocket size. This is one of those rare occasions when complex new technologies actually empower ordinary people—not everyone in the world has access to clean water—and I was looking forward to testing mine out in the Haw.

Did I say that the river had been mostly cleaned of pollution? A few days before setting out I read that just this September a Burlington company had leaked 1,4 dioxane into the Haw River. Used in paint strippers, dyes, greases, varnishes, and waxes, 1,4 dioxane causes respiratory irritation, drowsiness, and cancer; it can also affect liver, eye, and renal functions. The city of Burlington found that the water leaving its wastewater treatment plant contained 1,300 times the EPA’s health advisory levels.

I would be hiking upstream of Burlington, and as the chemical had been dumped down the drain, I likely wouldn’t encounter it north of the treatment plant. And it would be gone by late October, anyway—but only because it had been carried downstream to Pittsboro, where residents unknowingly drank it.

But this is not an unusual occurrence. The remaining industry in this region still improperly disposes of chemicals in wastewater, including PFAs, so-called “forever chemicals.” Even worse is chemical runoff from farms, roads, golf courses, and private lawns. And the biggest source of pollution, period, is sediment—eroded soil from plowed land and construction.

Sediment, my little pocket filter will handle. Protozoa? Bacteria? Check. But your lawn chemicals run off in a rainstorm? Nope. In the jungle, I’d have nice safe drinking water. In suburbia, forget it. I’ll try out my miracle technology another time.

Someone is always downstream. A river basin, like the sunrise, is a fact of nature. And we are too often more pigheaded than clever.

But let’s end on a more positive note.

The new section of the Haw River Trail at Shallow Ford was established by Robert O. Lake and Barbara J. Lake-Harrison, whose grandfather was a black farmer who once owned 400 acres along the Haw. In honor of their mother, Lillian Elizabeth Johnson-Lake, who (the trail marker tells me) “grew up in a farming culture where she learned to love people, the land, and nature” and died too young, they named this trail the Lillibeth Corridor.

They also donated a bench, which sits above a cascade and bears this inscription:

Tired feet, weary souls, come sit awhile and rest by these tranquil waters; taking in the beauty of nature; and reflecting on the wonders of life. When you are sufficiently refreshed and ready to continue your journey, take with you the peace and serenity of this place and pass it on to fellow travelers along the trail.

When Lillian Elizabeth Johnson-Lake was born in 1912, about a third of North Carolina’s farmers were black, and about a third of them owned their own land, which is far from parity but more than you might expect at the height of Jim Crow. In fact 1910 was the peak of black farm ownership in the U.S.; it has declined ever since.

And so this trail and this bench serve also as monuments to another kind of community, of work, of life now gone. But they are quiet, unassuming monuments. They do not shout at you for justice, they do not even whisper laments; they only invite you to stay awhile.

It seems to me that there ought to be fewer grand monuments in honor of grand people and more unassuming kindnesses in honor of unassuming people. Kindness alone won’t make the river potable, but I'm grateful for it nonetheless.

Notes and further reading

Though I may live a thousand years, the title of this post is almost certain to be the only reference I ever make to a Dave Matthews Band song.

The map of North Carolina river basins is by the author, tweaked from a version originally published by LEARN NC in 2010 (or thereabouts) as part of the North Carolina Digital History project and now re-licensed Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0. The map of the Haw basin is Cape Fear River Basin-1 (Deep and Haw River Basins) by the North Carolina Department of Water and Air Resources, 1968, via UNC Libraries.

You can learn much about the Haw River, including history, geography, threats to its ecology, and current conservation efforts, from the Haw River Assembly. On recent revitalization efforts in the region see Bruce Ingram, “A River on the Rise,” Wildlife in North Carolina, July–August 2019, pp. 22–27. The excerpt from John Lawson’s 1709 A New Voyage to Carolina is available via Gutenberg.

On pollution of the Haw in fall 2023, see Abigail Hobbs, “Haw River continually contaminated by Burlington companies,” Elon News Network, 9 Sept. 2023. You can read the Material Safety Data Sheet and EPA fact sheet on 1,4 dioxane for yourself, if you like; they are rather more specific than the Proposition 65 warning sticker that comes on every single item I buy from Woodcraft.

On the rise (after the Civil War) and decline (after World War I) of black farming in the South, see Loren Schweninger, “A Vanishing Breed: Black Farm Owners in the South, 1651-1982,” Agricultural History 63 (Summer 1989): 41-60. According to the 1910 Census of Agriculture (volume 7), there were then 253,725 farms in North Carolina, of which 64,456 were operated by blacks; of these, 32.8 percent owned their land, or about 21,000. (For comparison, about 32 percent of North Carolinians overall were black.) The percentages were somewhat lower in Alamance County; there 30.3 percent of residents and 23.6 percent of farmers were black. The Census of Agriculture asks questions of operators not owners, and I couldn’t find by-county data on ownership—which is not to say it isn’t out there, just that I called off the search. It was bedtime, and I had another hike to plan.