Falls of the Neuse

A summer morning's hike along Falls Lake officially starts my trek.

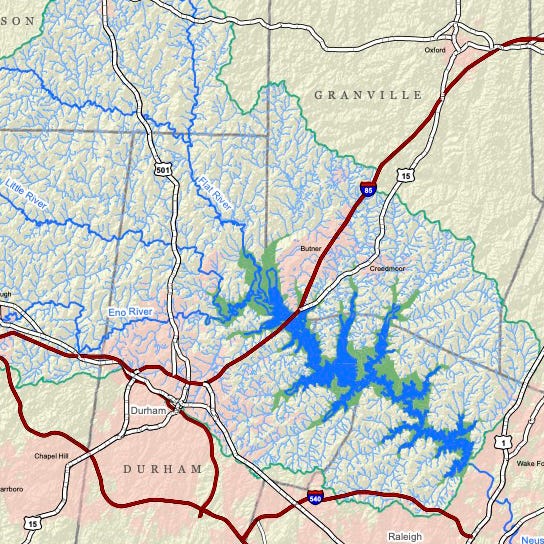

Drive north out of Raleigh up Falls of Neuse Road and you will find… not falls, but a dam. The cascades and rapids that once marked the transition from Piedmont to Coastal Plain lie submerged by a lake. Falls Dam was built forty years ago, and the lake spread out behind it, spreading fingers along streambeds, but the name survives.

It was here I began my first stage of the Mountains-to-Sea Trail. My daughter was heading back to college in a week, and we wanted a day hike somewhere we hadn’t been before, something we could finish before the heat of an August afternoon. We’ve hiked a lot of miles together over the years, criscrossing the state on field trips for homeschool science, and to have her company seemed the right way to start. For those of you scoring at home, this is Segment 10, Westbound Mile 0.0 to 3.6, Day Hike A.

So, the falls. East of the Appalachians the land changes from hilly, rocky Piedmont to flat, sandy Coastal Plain, not gradually but suddenly, where hard metamorphic rock gives way to more easily eroded terrain. Millions of years ago this escarpment was North America’s coastline. Now rivers fall with the land, and so the “fall line” (geologists might prefer “zone”) marks the place where, traveling by water upstream from the coast, one has to stop. Falls thus invited trading posts, as well as mills to harness the power of falling water. Trading posts and mills attracted settlement. In time roads connected these towns. Railroads followed, then highways: US Route 1, and later Interstate 95. The fall line doesn’t appear on most maps, but US-1 is a good approximation.

At Falls of the Neuse the river still runs rough when the dam is opened, but the falls, such as they were, are gone. In the nineteenth century they made prime real estate for a paper mill, but when electricity replaced water power the ancient desire to harness the river gave way to the modern need to control it. In the 1930s a dam was proposed to control flooding along the Neuse; Congress approved the plan in the 1960s, and the Army Corps of Engineers finished construction in 1981. The lake provides drinking water for Raleigh, as well as recreation. But the main idea, and the reason the feds got involved, was flood control.

The Neuse River has always been prone to flooding. It forms northeast of Durham from the confluence of the Eno, Little, and Flat Rivers and empties into Pamlico Sound 275 miles southeast, its entire watershed falling within state lines. Most of its bed runs through the flat Coastal Plain, where a rising river spreads quickly: when it floods, it floods. At Kinston the river reached flood stage nearly every year between 1930 and 1983, when Falls Lake reached its present level. Ten times in the twentieth century the peak flow was seven inches above flood stage, a “major” flood. Hence the dam.

But control is a dangerous word when it comes to natural systems. The promise of a flood-free future and a series of droughts in the 1980s led to development along the floodplain just south of the dam near Raleigh, which made it harder for the Corps to time the release of floodwaters without causing expensive damage. After a pair of major hurricanes in the late ‘90s caused catastrophic flooding downstream, Kinston residents felt, with some justification, that they had gotten what wealthy, powerful Raleigh had spared itself. Some who lived along the river hadn’t bought flood insurance because they believed the dam would prevent flooding. But the dam only stems about 30 percent of the Neuse river basin above Kinston; the rest is out of the Corps’ hands.

Perhaps mitigate is a better word. Flooding remains a problem. When Hurricane Matthew dumped a foot of rain on eastern North Carolina in the fall of 2016, coming on the heels of thunderstorms that had rivers already running high, the Neuse at Kinston reached 28 feet, twice its flood stage. The damage was enormous, and 24 people drowned.

There is a dam, anyhow. But it will take more than that to keep people safe from hurricanes and floods… if such a thing is ultimately even possible.

The lake is pretty. There is fishing here by the dam, and boating elsewhere. The protected land makes habitat for wildlife. On this Wednesday morning in August, the lake was quiet.

Westbound, the Mountains-to-Sea Trail winds along the lake’s southern edge from Falls Dam upstream to the Eno River: not what you would call a direct route, and today’s walk took us only as far, on the Corps of Engineers map above, as the tip of the lake’s eastmost lower finger before we turned around. Still there is plenty to see.

Not far west of the dam a section of longleaf pine forest has been replanted, and is maintained by regular burning—not too recently, it appeared, for though the trees’ lower bark remained visibly charred, saplings had grown back. Fire is part of this ecosystem. It clears out underbrush and nourishes the soil; longleaf pines are adapted to moderate fire, as are the other plants and animals of the forest, which return quickly after a burn. There will be time later to say more about the longleaf pine; for now, enjoy the scenery.

I need to read up on the geology of Falls Lake — on geology generally; it’s a serious gap in my studies. I do know that the eastern part of the lake lies on harder rock than the western part, and is therefore narrower and deeper. Above the dam boulders hulk just off the trail. Leucogneiss, maybe? Don’t quote me on it.

The trail leaves the lakeside to follow Honeycutt Creek far enough upstream for a bridge. (Exactly where the creek ends and the lake begins is a judgment call.) The streambed has the tumbled-boulder look of the western Eno River and its creeks, like mountain streams. Maybe gneiss again. As I said, I need to read up on geology, and I need to start inspecting the rocks more closely.

Venturing down to the lakeshore, where I neglected to take a picture, we heard a woman on the trail calling “C’mon! Hup!” We turned to see three half-shaved puffballs trotting on the ridge: white shi-tzus with their summer cuts, tagging along off leash. “Your little platoon!” I said when we met again coming back, by which time the dogs were just as enthusiastic but somewhat muddier. “Yep, my entourage!” she agreed. And I thought: what a lot of bathing.

I wanna be a golden retriever (I wanna be a golden retriever) Swim in the lake and smell like beaver (Swim in the lake and smell like beaver)

Later, in the insect-buzzed leaf-rustling stillness of what seemed deep woods, a distant fossil-fuel roar, then another. Leaf blowers. One may be a homeowner, but two mean a lawn service. Someone paid a great deal of money for lakefront property to live in this sylvan paradise—and requires manicured lawns. We glimpsed through trees the wannabe-Italianate trimmings of the mid-sized mansion, the flat expanse of monochrome grass standing out from the mixed and mottled tones of the forest like a straight line in the landscape.

Returning, we ate lunch on the shore by the dam, perched not quite comfortably on rocks. I thought of summers in college when I worked at a research lab at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, writing FORTRAN code to model electrodynamics for ballistics research. (No really.) The Proving Ground sits on a far finger of the Chesapeake, and middays I used to leave my windowless air-conditioned cave and walk out by the bay, stopping on piles of rock and construction debris to watch the birds and eat my lunch. The rocks, the bagged lunch, and the low-tide smell brought those days back—and, probably, the presence of army-base signage and construction.

Then a bald eagle swept down from a high perch to snatch a fish from the water and in what seemed a single swift motion flew to another treetop to eat it. A day’s work for the eagle, a masterful performance for us. Such grace, such power — such vision, to see movement in shallow water from a hundred feet away! I saw no bald eagles on the Chesapeake thirty years ago; they were still endangered, still recovering from a century of hunting and decades of DDT. Now they have made a home on Falls Lake. Bald eagles were never part of the plan for for this dam, but all our acts have unintended consequences, and some of them, glory be, turn out for the good.

Notes and further reading

On Falls Dam and flooding along the Neuse see Danny de Vries, “An Historical Ecology of Flooding, Uncertainty, and the Falls Lake Project,” Presentation to the WRRI 9th Annual Conference, April 4-5, 2006. On the impact of Hurricane Matthew see Corey Davis, “Five Years Later, Five Lessons Learned from Matthew,” North Carolina State Climate Office, October 7, 2021. The map of Falls Lake is from the Falls Lake Master Plan developed by USACE Wilmington and the State of North Carolina; the USACE’s website on Falls Lake gives additional information. For a broader perspective, in The Control of Nature (1990), John McPhee has a chapter on efforts to keep the Mississippi flowing within its present banks.

As I plan more hikes along Falls Lake I’ll be reading NC Geology’s website on the region.

If you’re not familiar with the story of the bald eagle’s return from near extinction, start with this Smithsonian magazine story.

I considered footnoting this essay, but decided this format is friendlier and equally effective for our purposes. Notes at the bottom will be my practice going forward. The research is fun, and I hope you enjoy the fruits as much as I enjoy the process!

Thanks, David,