The greenway in winter

A mostly pleasant walk along the Neuse River that was more interesting, and more memorable, when it was a little less pleasant.

After four months in which our only significant rain came from a single tropical storm, December turned dramatically wet. Ten inches fell in the five weeks centered around the solstice, most of it in a few weekend drenchings. By early January the Eno River had turned the state park into a swamp; after trying four trails and finding them all impassable my daughter and I gave up our belated New Year’s hike and went out for burritos. The glorious thing about getting out in nature is the possibility—indeed the likelihood—of being surprised. This is also the difficult thing about getting out in nature.

But the Mountains-to-Sea Trail is not always—perhaps not even primarily—about getting out in nature. It is about seeing the Great State of North Carolina, much of which is not what you could really call natural... even when it’s made to look that way.

Segment 11 of the Mountains-to-Sea Trail begins at Falls Dam, once the Falls of the Neuse River, now its headwaters. This is where I began hiking the MST last August, heading west along Falls Lake through Segment 10. Falls Lake is so convenient and so pleasant that I’ve been doling it out a little at a time, and saving most it for spring and summer. Still on the coldest and shortest days of the year I wanted to stick close to home, so at the end of November I returned to the dam and resumed my weekly hikes in the other direction, heading downriver on the right bank of the Neuse.

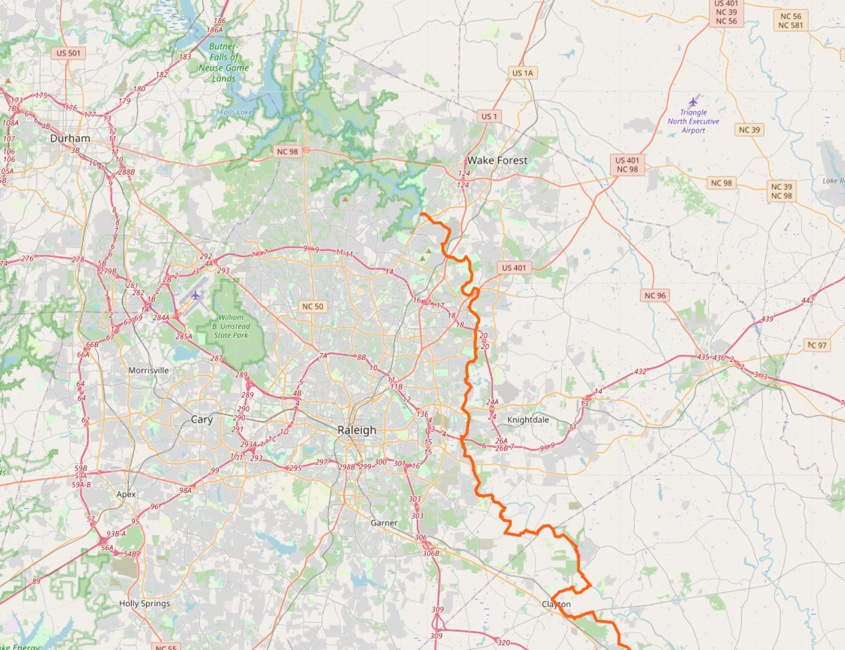

The trail here is the Neuse River Trail Greenway, which runs 27.5 miles from Falls Dam to the Johnston County line, skirting the eastern edge of Raleigh before emerging into farmland. It is paved, maintained by the city parks department, and at the county line it connects to the Clayton River Walk and the Sam’s Branch Greenway, which take you as far as Clayton. From Wake Forest to Clayton, from Raleigh’s northernmost bedroom community to its southernmost, you can walk 35 miles without getting your feet wet or dodging cars. At least in theory.

The Neuse River Trail is... pleasant. The pavement is a boon in this season of mud. Smooth, level ground makes fast walking—while I’m not exactly in a hurry on these walks, making three miles an hour instead of two and a half saves time for exploration without costing me sights along the way. You don’t pass many people on winter mornings, but they are polite if not openly friendly. The dogs are curious and leashed. Bicyclists nearly always signal when passing, as the signs ask them. The path has grassy borders, and there are trees, mostly bare now, but the stubborn brown-paper leaves of beeches and the green splashes of holly are always welcome.

It is pleasant. It is safe. It is unsurprising and thoroughly tame. It is, after all, a park. And it is a narrow park, with nowhere to walk except the greenway itself and, at least in the city, too little buffer to feel entirely natural. Upland is rarely public and often developed, the woods sometimes deep enough for the knocking of woodpeckers but never dense enough to provide cover for a pit stop. The eponymous river is mostly invisible, hidden even when close at hand by a natural berm, which mitigates flooding but also sightseeing. Not that flooding is much of an issue here. When I did glimpse the Neuse, at least in December, I found it as tame as the greenway. Consecutive weeks of heavy rain had only filled the lake behind the dam, which meted out the impact just as it was built to do.

In places even the land along the river is privately owned, with signs warning you to stay on the trail. And the trailheads are often miles apart, so that once you are on the greenway, it may not be easy to get off again.

The city is no less strongly felt here for its being hidden—more strongly felt than the river, certainly. Its management, its desire for control, are always present, so that what is not controlled seems to have been put on notice. The river subdued, the birds subdued, the hiker with only one path before him, hurrying on to the next trailhead.

A greenway is the sort of thing for which I suppose I am too contrary to be appropriately grateful. Greenways carve space for pedestrians from a world of cars and trucks, a space for humans in a world dominated by machines. But that they are needed is itself a condemnation of the society we have built, and to accept their need uncritically is to accept just as uncritically the domination of machines over people. It is to dismiss the idea of a walkable city, a walkable world, as implausible.

But the deeper problem is that a greenway emerges from the same logic that produced the rest of our transportation system. A greenway is only a freeway inverted: a limited-access pathway that exits the city here and emerges there, bypassing everything in between; replacing the haphazard, the winding, the happenstance with the direct, the simple, the dull. Both offer an illusion of freedom—but only an illusion. The illusion of freedom on a freeway shatters when the gas light comes on in the middle of nowhere—or when someone wrecks and blocks a lane, and the eight-tenths of a mile to the next exit stretches ahead like the Silk Road through the Gobi. The illusion of freedom on a greenway shatters when you have to arrange a long-distance walk around the hope of a port-a-john—or when unannounced highway construction closes the path and you can only turn around and walk two miles back to the last trailhead.

I am, as I said, being contrary, and probably overthinking the matter, which is a thing that can happen when you walk long distances alone. Most of Raleigh’s greenways are more integrated into the city and less isolating. They’re great for a bit of exercise or for walking the dogs, and hiking the NRT sure beats walking along Capital Boulevard. All things considered, I’m glad of them, and I always vote yes on parks bond issues. But on this segment of the Mountains-to-Sea Trail the walks I remember are those when the unpredictable chaos of nature or the city broke through.

When I look over the spreadsheet that tracks my progress, I can remember details of almost every hike, but the days on the Neuse River Trail blur together. I remember Nick Reston’s birds of prey painted on sewer outcroppings, though I could not tell you where to find them without cross-checking the photo metadata with my spreadsheet. I remember the bridges over the Neuse, where I could stand and watch the slow-rolling water, and one long boardwalk over a marsh early on a frosty morning, which even in winter (especially in winter!) was the loveliest thing I saw on the MST in Wake County.

I remember more strongly the long detour around sewer work: the empty browned-out golf course, the city streets, the clutch of townhouses. The pond with its walkway and gazebo and the young man in shiny clothes dancing by himself in the barely thawed hour after dawn. The Circle K on New Bern Avenue where I stopped for a cup of coffee—I did not especially need coffee, but the morning was cold, and I have said before how nice it would be to have the option, and why pass up a restroom?—and was taken by the clerk, I believe, for a homeless person. (The clincher, probably, was paying with cash.)

The Sheetz where I bought a sandwich and wished I hadn’t. The toddlers on the playground at Anderson Point Park.

South of the city the greenway becomes less like a park, less controlled, more like an open rural road, albeit one for humans instead of automobiles. The river comes more continuously in view, the woods grow thicker. For a mile or two the path parallels a farmside road almost as a sidewalk. Wetlands buffer the river. By January, after yet more soaking rain, and after the dam, I presume, had released some of the waters, much of the land between the path and the river was muddy swamp with a scrim of ice. In one place the trail was flooded, and the surface frozen. I picked my way through as best I could, poking at the ice with my stick to test the water’s depth, and managed to keep my socks dry. I was grateful for good boots, but also, perversely, for the icy marsh. A hike ought not be too convenient.

On my last day beside the Neuse I passed into Johnston County. It was the last week of January, almost halfway to the equinox. A warm front over the weekend had brought more rain and unseasonable warmth, and though a morning chill lingered, the air and the light had changed. The birds were more active, the moss was greening. Shortly before noon, passing another marsh, I heard a long, low crr-rr-rr-iiiiiick? And then another: the first spring peepers waking, warming up their voices for the coming chorus. I had left the shadow of the city at last, and spring was on the way.

Notes and further reading

The long-distance, controlled-access greenway also reminded me of something I wrote several years ago about highway travel and early posters advertising the London Underground: “Travel in the Magic City,” on Front Porch Republic. This placelessness-in-place is a thing that fascinates me, but if you’re bored with it, no worries: we’re probably done with it for awhile.

"Keep Out!" VS the roaming convention British people enjoy across the Isle (for the most part).

My favorite line - "A hike ought not be too convenient."