Hidden gems of Guilford County

Stopping by parks, and learning that I need to plan my detours ahead

As of October 23 I have finished four day hikes in Segment 9, covering 22.4 miles of the Mountans-to-Sea Trail and walking 49 miles total. I have walked on quiet country lanes, well-traveled back roads, a gravel road and a numbered highway. I have walked through a soccer park, an industrial park, and three parcels of parkland that are not called parks. I have seen several herds of cattle and one of goats, various horses, a pair of donkeys, two flocks of chickens, one blue heron and a lot of dogs, some friendly, some best tied up. I have been ignored by a myriad of motorists and had pleasant if brief conversations with a golf course maintenance man, a homeowner unloading four garbage bins from a cart, and a county parks employee ineffectually deodorizing a vault toilet.

I have been hailed from a driveway by someone who spotted my backpack, guessed I was “hiking the trail” and asked how far I was going. I have been stared at by cows, which was oddly unsettling until I realized that they probably felt the same way about me. I have been barked at joyfully by a pair of large dogs—American bulldogs?—whose owner assured me just wanted to get out and walk with me. Thwarted in that desire, they beat each other up instead. As dogs will.

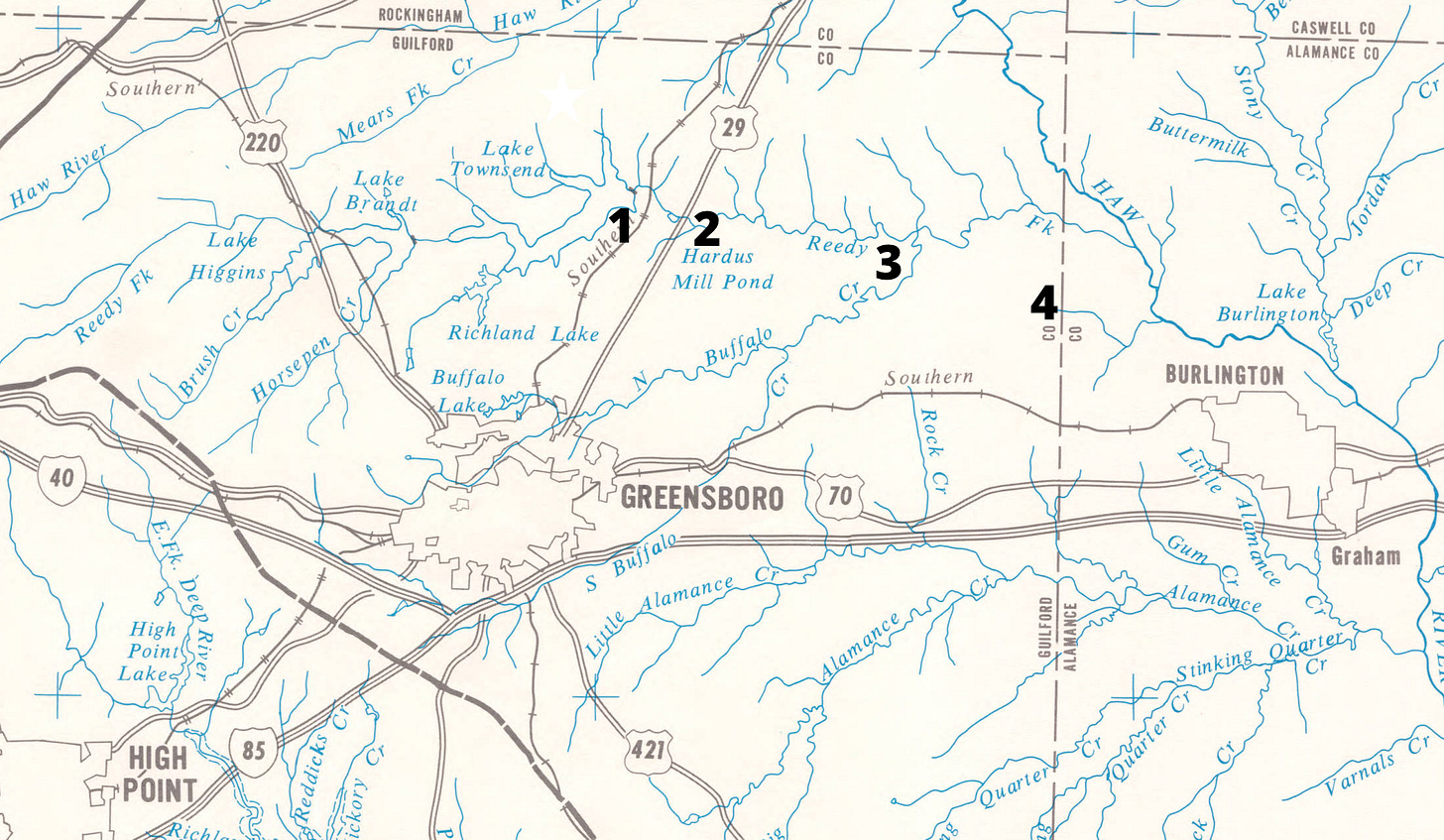

But I want to say a little more about the parks, before I leave Guilford County. For now, anyway—I’ll come back to hike the western half, through Guilford Courthouse Battlefield and along the south end of two reservoirs. Segment 9, where I picked up, begins at the east end of Townshend Lake, at Bryan Park (#1 on the map below), which is not a park but a soccer complex, and almost entirely follows roads from there to the Alamance County Line.

Walking on country roads, as I wrote last time, it can be difficult even to find a place to stop and tie your shoes or dig a granola bar out of your backpack, let alone actually rest. Even on quieter lanes that make for pleasant walking, the psychological push to keep moving can interfere with what ought to be my goal of looking around.

So the parks are a blessing. When the trail runs through or by a park, I try to take advantage of it. The trailheads, at least, are usually on parkland, for the simple reason that they have public parking lots where you can leave your car, or at least a gravel pull-off. Walking from one park to the next, I’ve gotten in the habit—a little too slowly—of scoping them out first to see what they have to offer. There is always something, even if it’s only a picnic table and a port-a-john.

Here’s what I’ve found.

My first day hike ended at a wisp of a trail through a little nature preserve, just a mile and a half long, newly opened last spring. From the overgrown barbed wire I gather that Hines Chapel Preserve was until recently a working farm, and there are patches of relatively young forest punctuated by old oak trees that may once have shaded a meadow. Now the trailhead is in a semi-residential neighborhood behind a preschool, which has its own path into the woods.

The trail runs along Reedy Fork, a tributary of the Haw River—about which more later—and it made a nice respite after a morning of walking through golf courses and industrial parks. The bench at my picnic spot is craft-made, which is a nice touch, though I’d have been content with a good boulder or a notch between tree roots.

The second hike took me to Northeast Park, but only long enough to use the restroom. Northeast Park has, in fact, a vast array of recreational opportunities of which I utterly failed to avail myself: “state of the art aquatic center, miles and miles of hiking, biking, and equestrian trails, athletic fields, picnic shelters, playgrounds, and open space.” There are also a carousel and a mini-golf course.

The MST passes all this by. The trails at Northeast Park are extensive but self-contained, and don’t connect further on. They are also long, and the trailheads are a good half mile back from the road, so that to explore the woods along Reedy Fork or Buffalo Creek would have extended my hike from ten miles to probably fifteen. In retrospect, I should have done it. I might at least have ridden the carousel. (Or maybe not; it was a Monday.) But that morning’s walk had been treacherous and unpleasant, and I wanted to get back. All I saw was the former home of the Gerringer-King family, with a sign helpfully reading “Farm House.”

I had walked past several working farms that morning, and would walk past several more on my next hike. All of them had houses that were, therefore, farm houses. This “Farm House” is only a museum, for educational purposes—or will be, when the renovations are finished. But it looks like someone’s idea of a farm house, because it is old; whereas the houses on the actual working farms just looked like houses. The fact that children from the city are to be driven past real working farms to be taught about the “farming heritage” of a hundred years past is an irony about which I could say much, much more, but as I have already said it, why not just read the book?

Nearby stands a ramshackle structure with the sign “Wood Shed,” the need for which might be obviated by just stacking some wood there.

I said that all the farms I passed had houses. There was one notable exception: Guilford County Farm, which consists of 600 acres leased by the county to local farmers for crops and cattle, plus another 120 house greenhouses growing plants for county parks, vineyards where volunteers pick grapes to give to food banks and shelters, hives of honeybees and a pair of rescued donkeys, hiking trails and fishing ponds. It is just what you might naïvely expect a “County Farm” to be. Even the cropland is hospitable to travelers, with mown paths along the fencerows. The Mountains-to-Sea Trail runs right through it, and it was the first time I have walked through a working landscape and felt welcome.

If you grew up in the South—or if you have ever listened carefully to the lyrics of old blues songs—you might know better. Once upon a not very distant time, the County Farm was the County Prison Farm, where nonviolent offenders served out their terms growing crops and raising livestock to feed themselves and doing landscaping and maintenance for county facilities. This was Guilford’s second prison farm, built in the 1930s to house black inmates; it was integrated in the 1960s, and prisoners continued working it in dwindling numbers until 2015. The decriminalization of public drunkenness in the 1970s cut the number of available inmates, and changing economics may have doomed the enterprise.

Walking up the road, you could not possibly miss the farm’s original purpose, for razor wire still guards the old stone buildings. But the inmates who built those structures from stone dug up in the fields are long gone, and their only successors are a herd of goats milling around the yard, bleating pitifully that they were framed. To find yourself walking on Breakaway Trail or Prison Run Pass would also be a clue, though Preacher’s Pass, sadly, has been renamed simply the Connector Trail.

Escaping through the woods, pausing to listen for the baying hounds, you might find yourself by a quiet stream not deep enough to mask your scent and decide just to enjoy it a few minutes before they found you. You weren’t going to get far, anyhow.

Signs along the gravel road announced free end-of-season grapes, pick your own, and cones led the way to the vineyard. A few small muscadines hung on amid the yellowing vines, and I picked one and ate it, just because it was there.

I had walked eighteen miles through Guilford County, and the most hospitable part of the trail was the prison.

Missing the carousel bummed me. I might at least have seen the thing, you know? I took a closer look at the trail coming up and found that, though I would be passing by some interesting places, I wouldn’t be passing through them. Breaking my two remaining day hikes in Segment 9 into three would give me time for side trips and malingering—and wasn’t this whole project supposed to be about seeing the state? Side trips and loitering are the point.

Especially when most of the walking is on roads that range from quiet unlined lanes to numbered highways. If you are going to feel for a mile or two that you are taking your life in your hands to get wherever it is you are going, then wherever you are going had better be good.

Coming up: a detour through another natural area, a visit to the Textile Heritage Museum, and a whole day of loitering along the Haw River.

Notes and further reading

The map of the Haw and Deep River basins (the upper portion of the Cape Fear River basin) was adapted in 1968 by the North Carolina Department of Water and Air Resources from a U. S. Geologic Survey map and is available via UNC Libraries.

Information about parks is oddly scattered. County websites may exist in multiple versions and be inconveniently consolidated, and much of what I want to know is on somebody’s blog. Northeast Park has pages of general information (including a photo of the carousel) and a separate website with information about the historic farm. Guilford County Farm has a county parks website, but its history as a prison farm I learned from an unsigned graduate project in public history from (I assume) UNC-Greensboro. The best place to learn about Hines Chapel Preserve, meanwhile, is from this hiking blog.

As a former Appalachian Trail thruhiker, I've been fascinated by the idea of an MST hike. The experience would be much, much different than the AT. My wife (also a thruhiker) and I have hiked a few MST sections, most notably the area around Falls Lake and up at Shining Rock in the mountains. I followed you on micro.blog and subscribed to your Substack. I look forward to more.