The changeable woods

Another hike along Falls Lake, the same and yet entirely different from the last one.

With its easy trails and frequent road crossings Falls Lake is great for unplanned hikes, and with a morning I could clear of work and a break from the heat I figured I would pick up where I’d left off last time and cover another three miles of trail. Six miles’ walking does not require a plan, a backpack, provisions, or even good boots, though as I’m trying to break mine in I wore them anyway. All I carried was one hiking stick, a pocket notebook and a pen. I felt naked.

To get to the trailhead I drove to the dead end of Possum Track Road, which would make a good story. Now my great-uncle Charlie lived out the end of Possum Track Road, it would begin, and carry on to include moonshine, an outhouse, and a nonlethal injury. But such a story would surely predate Falls Dam, and Possum Track didn’t end here before the dam flooded the Neuse River to make the lake. From a 2013 article in the Raleigh News & Observer:

Before the dam project got underway [in the 1970s], Possum Track took a winding route along the Neuse River and connected to Falls of Neuse Road near where the dam stands today…. Now Possum Track Road comes to an abrupt dead end just short of the lake, with a dirt path continuing to the water over broken chunks of asphalt from the long-gone road.

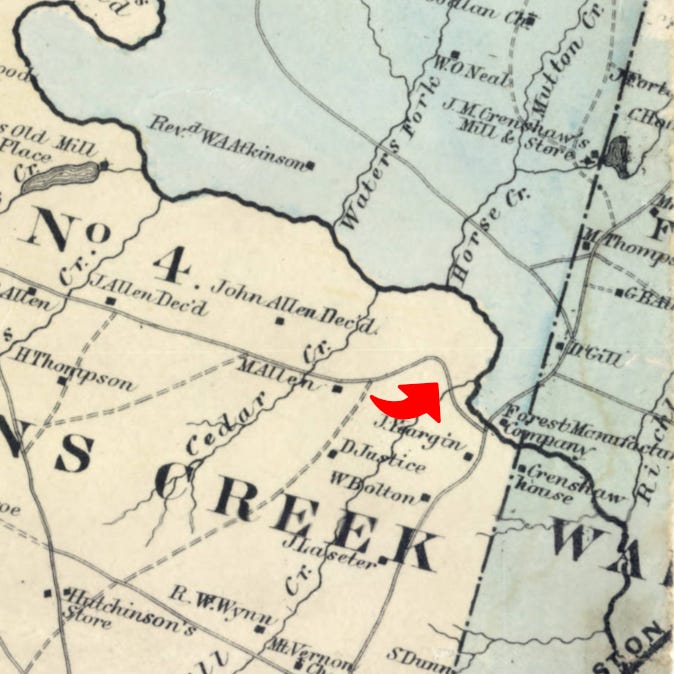

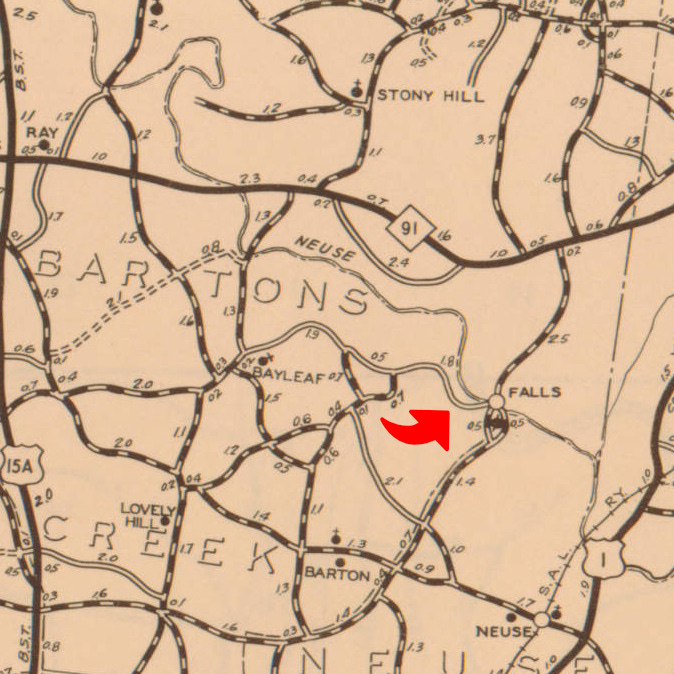

Though it isn’t labeled, I believe that you can see Possum Track on these old maps from 1871 and 1936, running south of the river and connecting to the north-south road near the falls. The arrows mark roughly where the road now dead-ends; everything from there east to the falls is underwater.

The road sign was down when I was here last month, and it hasn’t been fixed: if you don’t already know where you are, the sign isn’t going to help you much.

It was a fairly ordinary hike, I suppose. Trails through woods, a few easy hills, wooden bridges over creeks, occasional dips down to water. Of course that’s like saying that the book I just finished has a plot and some characters, or that you’d like this friend of mine who has two hands and a face. What makes a walk interesting is the details, and those are hard to capture succinctly: you wind up with the blurb on the back cover or an online dating profile, which even if written with honest intent winds up a little sketchy.

Start with the weather. After a rainy weekend Monday dawned still overcast, and when I made my way down to the water’s edge after a mile and a half of hiking the water was all gray reflections. While I stood on the little sandy beach the clouds broke, a patch of blue grew, and the lake, rippling blue, took on the day’s new character.

By the time I reached the next trailhead at the causeway over Cedar Creek, the sky had almost completely cleared. What a difference an hour makes! It seemed a different day, and the water, almost perfectly still where the causeway backs it up, reflected the change.

And this was still mid-morning, on the same day. By afternoon the light would have changed again, and still again by sunset. In a month the sun will come from a different angle, and the turning leaves will give the water a golden cast. If I walked this trail every day for the year, I would see the lake take on thousands of different aspects. Hence Monet painted the same water lily pond two hundred fifty times: he could have painted it two hundred fifty more and still not exhausted the possibilities.

Then there are the flowers, which change week to week with the seasons and mile to mile with the terrain. They want more or less sun, lakeside or upland, richer or poorer soil; they may bloom for a day or a season. I walked a only a couple of miles away in late August, but today I saw three little gems I hadn’t seen last time out: blue mistflower, Virginia meadowbeauty, and common elephant’s foot. The meadowbeauty flowered at the lakeside where I took the first two pictures above; it was while I was studying the flowers that the sky cleared. The others grew by the trail.

The next day I saw that mistflower volunteered in a woodsy spot behind my house. I am pretty sure it wasn’t there a week ago: this must be its time.

The forest has a cycle beyond the seasons. The land by part of the trail was logged a few years back, and the forest is returning.

The phrase “a forest of little pines” came into my head, from Wendell Berry’s poem “The Mad Farmer Revolution,” in which the eponymous farmer “threw a visionary high lonesome on the holy communion wine.” Having thus “drunk his fill of the blood of a god,”

He plowed the churchyard, the

minister’s wife, three graveyards

and a golf course. In a parking lot

he planted a forest of little pines….

He goes on from there, flowers springing up in his tracks everywhere he steps, sowing and reaping “until all the countryside was filled with farmers and their brides sowing and reaping.”

These pines sowed themselves: rampant, wild, scrambling for light, mocking the slow-growing hardwoods that will, tortoise-like, succeed them in the end. In a few years they will shade me; in ten the poplars and sweetgums will catch them up, and in twenty or thirty or fifty they will fall and give way to oaks and hickories. The weather may change in an hour, the flowers in a month, but to watch the forest succession is a project of decades.

To appreciate this changeability one has to know a place, or at least to try to. I walked the same acre of woods every day for seven years, and a trail by a river almost every week for about that long, and the light of each discovery was, like the stars in the sky, one more pinprick in the vast darkness of my ignorance. I learned enough to feel my way along familiar paths; I had an idea what to expect and when to expect it, but I was often enough surprised. And that was one place. Give me a different forest on a given day, say spruce pine forest on a mountainside in early June, and it’s just a pretty picture again. Having come to come to know one place over months and years, you may at least sense the changeability of another, merely in passing, even if you don’t understand it. You know, at least, that the snapshot is only a snapshot. You know enough to wonder. But even to know that much requires sustained attention.

As I’ve observed on previous hikes along Falls Lake, there are houses visible from parts of the trail. If the real estate here isn’t quite waterfront, it’s close, and it backs up to protected natural areas, which this near a midsized city is worth a small fortune. A quick search of Zillow for the streets behind the South Shore Trail (on which the MST piggybacks) finds houses of four to seven thousand square feet on two-acre lots worth upwards of $1.5 million, as well one available to rent for a mere $11,000 a month. Seeing the expensive architecture and expansive lawns through back fences I find myself wondering about the people who live there. Do they use the parkland, or do they just like the quiet (apart from their lawn crews) and the prestige? Do they walk their dogs out here, at least? Do they take time to pay attention, or is the forest just a kind of wallpaper? I don’t know, but the wide lawns and high fences suggest less that I’ve been fenced out than that the owners have fenced themselves in. They give the impression that someone has spent a great deal of money to live in the woods without actually living in the woods.

On a road that predates the lake are a few older and much smaller houses, still a stone’s throw from the parkland and a quick walk to the water but on land apparently less desirable. One caught my eye: two stories, brick and blue paint with a matching outbuilding, multiple birdfeeders, whirligigs and a handmade mailbox, the yard fading quickly into open woods. A black and white dog barked from a second-story deck, easing his front paws onto a short quick-sloping roof, then thinking better of it and easing back up. This place looked like it belonged, and as if someone who lived here might belong, and I felt a kind of appreciation for it.

Maybe my instincts are wrong on both counts. Maybe the fences are only for dogs and the ornamented yard all the entertainment anyone feels they need. I’m not apt to go knocking on doors to find out. Let’s just say that I hope they all appreciate what they have. A patch of woods may look ordinary, but it never is.

Notes

On Possum Track Road see Colin Campbell, “Ghost Roads Disappear into Lake,” Raleigh News & Observer, January 5, 2013, republished at Ghost Lakes; and “Hidden History: Exploring the Abandoned Highway 98 Beneath Falls Lake” from WRAL news. The maps showing Possum Track Road are the Map of Wake County by Fendol Bevers, 1871 (detail), via UNC Libraries, and a 1936 North Carolina County Road Survey of Wake County (detail), also via UNC Libraries. You can also see it on Google Maps.

Wendell Berry’s poem “The Mad Farmer Revolution” was the first of his “mad farmer” poems, predating the more famous “Manifesto: The Mad Farmer Liberation Front.” The copy at hand is in his New Collected Poems (Counterpoint, 2012), p. 137, but it originally appeared in Farming: A Hand Book (1970), which I seem to have given away at some point. I hope the recipient has enjoyed it.