Sisyphus of the Eno

The excitable waters of a familiar river turn sultry in a land of prairie flowers and strange apparitions.

Today I arrived at a perfectly nice city park, strapped on my little backpack and headed off in the wrong direction. A sign, hand-lettered and photocopied, warned that all the trails in the park were closed due to storm damage. But I was leaving the park: crossing the river on a footbridge, scrambling down to the water, past the red-mud embankment and concrete pillars under the rush-hour traffic of Roxboro Road, and up again to a thin crease in the tall grass between the river and the city sewer line. If the hulking sewer vents faintly stank on this warm morning, at least it was impossible to get lost, for as the ancient poet wrote,

If your heart lies by the sea, Then you must take the easement road, For sewage always flows downstream.

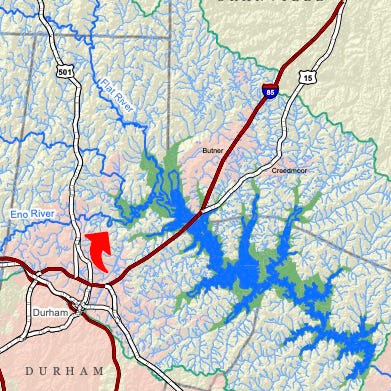

I am upstream of my previous walks, heading down the Eno towards Falls Lake, about five miles from West Point on the Eno to Penny’s Bend. This is the only part of Segment 10 of the Mountains-to-Sea Trail not featured in a day hike... possibly the sewage has something to do with that.

I know the Eno almost as if it were my own back yard—part of it, anyhow. For almost twenty years I lived just three miles from Eno River State Park, through which runs fifteen miles of the eponymous stream. For much of that time I went out almost every week, hiking alone or with my basset hound Sadie or running trails before my knees hit their best-by date. I walked along that stretch of river in every season, dry years and wet. I can close my eyes and see the rapids and runs, the little cascades, the swimming holes, the calm waters where turtles sun themselves on downed trees; the banks, mostly steep and rocky, rising up to hardwood forest.

The river at my right this morning is not my river. Oh, my river flows into this one. It bears the same name on maps. But it is changed the way some old friends are changed, and you think, who is this person? And changed not gradually as it makes its way to the sea, but rather suddenly. It broadens. It slows. It no longer in a hurry; it embraces the landscape. Except where rocks have tumbled into its path only the drift of fallen leaves marks its progress.

The river, in short, feels old—and yet its bed is almost half a billion years younger than the rocks upstream. I’ll do my best to explain. If you are a geologist, please be forgiving.

Six hundred million years ago the land around the Eno’s source lay under water, off the coast of what eventually would be North America. The sliding of one ocean plate beneath another created a subduction zone like those that now rim the Pacific, where magma bubbled up through the sea and formed volcanic islands. Slowly, because six hundred million years ago there was no life on land and thus no plants to anchor the ash and keep it from eroding; but in time the rocks hardened into what would become this part of the Piedmont. In more time they merged with the rest of North America and were folded and changed by heat and pressure when Africa slammed into the coast and thrust up the Appalachians. Then, as the continents began to drift apart again, the Piedmont eroded. Sediment ran towards the sea, built up into sandstone and siltstone, and formed the Coastal Plain.

From its source to my rat’s crossing beneath Roxboro Road, the Eno cuts through metamorphic rock with its origin in those ancient volcanic islands, a region geologists call the Carolina Terrane. East lies a Triassic basin built up by sediment four hundred million years later. Cross that line from (in essence) transformed magma to packed runoff and the river more easily erodes its bed, spreading out with the land and slowing. Upstream, forced to cut sharper channels, it runs faster and rocky.

In a sense, this is a different river than the one I know so well. That river is young, scrappy, and hungry—unlike its ancient country, which is hard and unforgiving. This one, flowing into luxury and ease, has grown lazy; at best relaxed and welcoming, at worst sludgy and sullen. The land still varies, but I feel what geology confirms: I have crossed a line.

Of course no life is entirely without struggle. Where the continents drifted apart magma welled up and intruded into the Triassic basin, hardening into diabase. Penny’s Bend, my destination today, is underlain by diabase; here the river detours south until it finds rock more easily eroded, creating a little peninsula.

Penny’s Bend is a more interesting place than I would have realized from a walk-through in August. Diabase is rich in iron and magnesium, and the soils above it tend to be alkaline, which fosters unique plant communities. Some of the grasses and flowers here are more typical of midwestern prairie, and the North Carolina Botanical Garden has managed the meadow by reintroducing native species. I would need an expert at my side to appreciate what I was seeing. Spring would be the time to see the wildflowers, and identifying grasses is beyond me. I did find blazing star, a purple aster native to prairie ecosystems. (The app on my phone said it was cylindrical blazing star, Liatris cylindracea, but the Botanical Garden has planted Southern blazing star, Liatris squarrulosa, so I assume it was the latter.) I’ll plan to go back in the spring—or, better, find a guided walk.

It was a Wednesday, and warm, and not a well-traveled trail. The woods were still, the meadow was still, the river was still. Even the signs of human activity marked absence. A city park with empty playing fields, empty picnic shelter, empty grandstand. A decaying tin-can camper abandoned in the weeds. A decrepit stable, broken stalls and rusting roof.

Walking mile after mile without seeing another living soul you may, as I have observed before, start to see ghosts. Worse, when you do see another living soul, you may wonder whether he, too, might be a ghost. A foothills creek skipping like young colts might focus your mind, but the ambling of a flatlands river summons dreams.

Maybe a mile east of Roxboro Road some accident of geology brings the river deeper into the land. My path lay too high above the water for an easy scramble, and the far bank swept up even more sharply, the red earth held in place by roots. On the ridge stood modest houses, older family homes with rambling decks and woodsy yards. Behind some of them wooden ladders ran down to the shore. Much of this river runs through parks; here, for some, it is an everyday presence.

In the middle of the current a man trudged upstream. Heavyset, gray hair unkempt, long pants wet to the knees, gloved hands. Rolling a tire.

Storm debris? Was he cleaning, retrieving, scavenging? To roll a tire up a rocky riverbed is not like rolling it on a road, even when the water is shallow. Bent to his task, moving deliberately, he did not see me standing on the far bank. I thought to call out a greeting, but the thought of my voice piercing the quiet made me uncomfortable, and what would I have said? I was too far away to offer help. He reminded me of someone I had known in passing, who died several years ago, and that, too, made me uneasy.

Irritably he shoved the tire into the stream, wiped his brow, heaved a sigh, righted the tire and resumed his labors.

I thought of Sisyphus. Does the river while he sleeps seize the tire and carry it back downstream, whence he must roll it again tomorrow? Is this man the Sisyphus of the Eno?

Maybe I wondered aloud, for I heard a grunt of assent. A weatherbeaten man stood by me on the trail, leaning on a stick. Face lined like a crumpled paper sack, ears grown large and red with sun, white wisps flying from a faded Wyatt-Quarles seed cap. Wad in his cheek. Eyes washed pale like sky reflected on a calm river, and piercing. I can’t remember what he wore. Overalls, I think. The eyes held me.

He spat ambeer into the weeds and looked at me. “You want to know the story,” he said. It was not a question. He shifted his weight, and what I had thought was an oak branch scavenged for a cane now seemed to be carved with weaving coils, like snakes.

The old man spoke in a singsong drawl, taking his time.

The sky god coveted the river’s daughter— The goddess of the dew, whose laughter Coaxed the birdsong from the dawn. You know the type. We called her Sundrop, left her packs of Nabs As offerings, though none remembered why. Well, The sky god glimpsed her bathing. Had to have her. Took the form of man, slicked back his hair, Stole a Thunderbird. Laid on the charm. But Sisyphus the fisherman, wandering The weedy bank, was witness to the crime. He saw the kelp-hair in the greaser’s arms, Heard the car door slam, the motor rev, Smelled the hair oil where he’d dropped his line. When soon enough the river sought his daughter The honest man told all. How could he not? The river was his life, his livelihood, and anyhow That hair oil stank. Alas, for his confession He earned the river’s thanks, and heaven’s curse. The river foamed and seethed in righteous rage. Rising up he flooded frontage road Where the lord of heaven had parked to make some time, Swept the T-bird onto rocky shoals, Washed his daughter safely to his arms. But the god of thunder sprang free of the wreck And shedding earthly form, revealed himself— Plucked trembling Sisyphus from the shore, And passed his sentence. The sportscar lay in ruins, All but one tire that drifted in the current. “Find it, foolish fisher, restore it to its frame, And I will let your mortal bones go free.” Honest Sisyphus did as he was told, Braved the current to the woven weeds Where the tire had tangled, freed it, rolled it Sedulously up the stream. Then he collapsed From sheer exhaustion. While he slept The sky god loosed the muddy tire once more And morning found the fisherman’s work undone. Thus heaven takes revenge on hapless souls. Sisyphus must roll his tire each day, And though the grateful river cools his feet And Sundrop sometimes gives him half her Nabs, They cannot intervene in mortals’ fate. The current must undo his work each night, For tires, like sewage, always roll downstream.

The old man fell silent. He shot a stream of ambeer into the weeds and glared at me. Sisyphus had rolled his tire around a bend; the tea-dark river ran alone. A question came to my lips, but when I turned back to ask it, the old man was gone.

Notes and further reading

Everything I said here about the geology of this region is drawn from the North Carolina Geologic Survey’s A Geologic Adventure Along the Eno River (2007), but you can find much (if not all) of the same information on ncgeology.com.

On Penny’s Bend see the Eno River Association’s information page on Penny’s Bend Nature Preserve; on restoration efforts see Emily Oglesby, “A River Runs Around It: Restoring the Rare Flora of Penny’s Bend” (North Carolina Botanical Garden, April 19, 2022) and “Planting Native Seedlings at Penny’s Bend” (North Carolina Botanical Garden, Dec. 12, 2022).

If you are not from around here you will not know that Nabs are packaged peanut butter-filled snack crackers, originally a Nabisco trade name, now applied more generally. Food and Wine explains.

As for Sisyphus, the story the old man told me echoes the one sketched in Appolodorus: The Library, Book 1, Chapter 9, translated by James Frazier (1921):

Sisyphus is punished in Hades by rolling a stone with his hands and head in the effort to heave it over the top; but push it as he will, it rebounds backward. This punishment he endures for the sake of Aegina, daughter of Asopus; for when Zeus had secretly carried her off, Sisyphus is said to have betrayed the secret to Asopus, who was looking for her.